A map for the soul's journey to God

The Ascent of Mount Carmel is one of the great masterpieces of St. John of the Cross and serves as the foundation for all his later writings, including The Dark Night of the Soul. In this work, he sets out to guide the soul along the steep and narrow road that leads to perfect union with God.

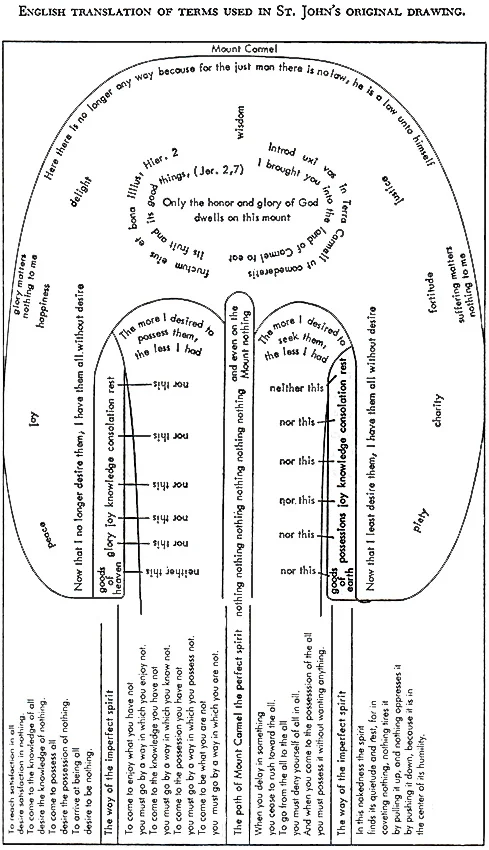

At the heart of the Ascent stands a striking image — the sketch of Mount Carmel, drawn by St. John himself. It summarizes in one vision the entire spiritual journey: the soul's gradual detachment from all created things and its ascent, step by step, toward the summit where God alone dwells.

The mountain represents the interior path of purification and love — a path that is demanding but luminous, leading to the total freedom of divine union.

The sketch of the Mount

St. John's diagram portrays a mountain with three paths winding upward. On either side, the broad and winding routes represent souls who seek satisfaction in possessions, feelings, or spiritual consolations. These paths do not reach the summit; they end in confusion or discouragement.

Only the narrow central path leads all the way to the top. Written along it are the words that summarize the saint's entire doctrine:

"Nada, nada, nada — nothing, nothing, nothing."

This does not mean despair or rejection of creation; rather, it means freedom from attachment — the letting go of all that is not God so that God Himself can fill the soul. At the summit of the mountain are the words:

"Only the honor and glory of God dwell in this mountain."

The sketch thus shows that union with God is attained not by accumulation but by stripping away. The soul climbs not by adding more, but by desiring less — until nothing remains but love.

The threefold way

The Ascent explains the journey symbolized by the mountain in three great stages — corresponding to the purification of the senses, memory, and will.

The Night of the Senses:

The soul learns to detach from the pleasures and consolations of the senses. It discovers that feelings and emotions, though good, cannot lead to God if clung to for their own sake. Faith begins to replace satisfaction.

The Night of the Spirit:

The purification deepens as the intellect, memory, and will are emptied of self-centered ways of understanding and grasping God. The soul is led into the "dark night" — not as punishment, but as preparation for divine illumination.

Union with God:

Having passed through these nights, the soul reaches the summit of the Mount — a state of silent, loving knowledge of God. Here, human desire and divine will are perfectly one.

The meaning of "Nothing"

St. John's repeated word "nada" is central to the Ascent. It expresses the paradox of Christian mysticism: only by letting go of all that is not God can we possess everything in Him.

He writes:

"To reach satisfaction in all, desire satisfaction in nothing.

To come to possess all, desire to possess nothing."

This teaching is not about annihilation of the self, but about transformation. The soul is purified not to be emptied into nothingness, but to become entirely filled with divine life. The "nothing" clears the way for the "All."

A theology of detachment and love

The Ascent teaches that spiritual growth depends on detachment, not as cold renunciation, but as love purified of self-interest. Detachment frees the soul to love God and neighbor more purely, without measuring love by comfort, emotion, or success.

In this sense, the Ascent is profoundly practical. It calls every Carmelite — religious or lay — to live simply, to quiet the heart, and to trust the hidden work of grace. It is the art of inner freedom, the path of faith rather than sight.

The summit: union with God

At the top of the Mount, St. John writes simply: "On this Mount there is only the honor and glory of God."

Here the soul, stripped of everything else, finds itself filled with peace. The will rests entirely in God's will; the intellect is illumined by faith; the memory is silent except for the remembrance of love.

This union is not something the soul achieves — it is what God gives when the soul has become empty enough to receive it. The entire ascent is, in truth, God's work in the soul, to which the soul cooperates through faith, humility, and perseverance.

The Carmelite way of ascent

For us Carmelites, the Ascent of Mount Carmel is not merely a book — it is the image of our vocation. The mountain stands as a symbol of the contemplative path: silent, steep, and sometimes shadowed, yet always leading upward toward the light of divine love.

Every act of detachment, every hidden act of love, every moment of faithfulness is a step on that central path. The Mount is climbed not in a single heroic act, but in daily fidelity to prayer and self-giving.

As we ascend, the "nadas" of St. John become not emptiness but freedom — the freedom to belong entirely to God.

The Mount in one glance

When you look at St. John's sketch, you are seeing his entire theology in a single page — the journey from self to God, from attachment to freedom, from multiplicity to simplicity, from darkness to light.

It is, at once, a map, a mirror, and a challenge. It shows us what the spiritual life truly asks: to desire only God, and to find in Him our All.

As he writes elsewhere:

"In the evening of life, we shall be judged on love."

And the Ascent is the path that leads, step by step, into that love — the summit where God alone is enough.